The views expressed in this post are those of the author and not necessarily those of Open Nuclear Network or any other agency, institution or partner.

* The article was originally published on ONN's Datayo platform.

On 22 May 2020, the United States formally submitted notice that it would withdraw from the Open Skies Treaty, beginning a six-month countdown that will finally end on 22 November 2020 with the US exiting the agreement.

The origins of the treaty can be traced back 65 years to 1955 when US President Dwight Eisenhower proposed an "open skies" plan to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev that would have allowed mutual aerial surveillance of nuclear facilities. The plan was ultimately rejected by Khrushchev and the "open skies" idea was not taken up again until the George H. W. Bush administration, which began to push for what would become the Open Skies Treaty in May 1989. Even then, the plan did not come into effect until January 2002 when it was ratified by Russia and Belarus.

Although Eisenhower's vision for "open skies" was limited to surveilling nuclear facilities, in practice treaty signatories could use the treaty's provisions to collect imagery intelligence anywhere in a participant's territory. As such, signatories could surveil conventional forces, nuclear facilities, or even civilian infrastructure. There was even discussion that the treaty could be useful for addressing environmental concerns.

As the US' withdrawal from the agreement draws near, it is worth revisiting the reason for the leaving Open Skies as well as what the future of the treaty might be without one of its key signatories.

Provisions and Mechanics of the Treaty

Open Skies provides a framework in which participating countries may conduct unarmed surveillance flights over the entirety of another participant's territory. The treaty stipulates that flights begin with the submission of a flight plan to a host country 72 hours prior to a petitioning state party arriving at an airfield pre-designated for Open Skies flights.

The host country may inspect the imagery sensors and equipment on the aircraft to make sure it follows treaty provisions (including the type of imagery equipment and maximum resolution of sensors) while host country personnel may also take part in the flight as well. Imagery taken on a flight is also available to all other signatories.

Flight plans may only be rejected due to safety issues, such as weather, while the flight must also be completed within 96 hours of the visiting aircraft arriving in the host country. The number of flights a host country may conduct, as well as the number of flights it must permit over its own territory, are determined by a quota system. A country's passive quota (the number of flights it must permit) roughly correspond to the country's territorial size while country active quotas (the number of flights a country may conduct over other participants' territory) are renegotiated on an annual basis but may not exceed the passive quota.

Disputes over the treaty’s provisions can be addressed either bilaterally or through the treaty's deliberative body, the Open Skies Consultative Commission (OSCC). The OSCC may, for example, make decisions regarding the accession of new members and the addition of new categories of censors allowed by the treaty. All these decisions must be made unanimously.

The OSCC's role in resolving compliance issues is somewhat murkier as the treaty states in Article X that the body will "consider questions relating to compliance with the provisions of this Treaty." In practice, parties work through the OSCC, including through a number of the body's working groups, and in bilateral or multilateral settings outside of the treaty's structures. However, there is no courtroom-like system for adjudicating disputes.

Why Not Closed Skies?

As conceived by President Eisenhower in 1955, Open Skies was to be a method for verifying adherence to various arms control and disarmament measures. Speaking at the Geneva Conference, Eisenhower stated "… we should consider whether the problem of limitation of armament may not best be approached by seeking -as a first step- dependable ways to supervise and inspect military establishments, so that there can be no frightful surprises, whether by sudden attack or by secret violation of agreed restrictions."

Though there were no real agreements to verify at the time, it is clear Eisenhower thought that transparency was paramount to avoiding "frightful surprises." Twenty seven years later, when submitting the treaty to President George H. W. Bush, Secretary of State James Baker wrote the treaty was designed to "enhance mutual understanding and confidence by giving all States Parties, regardless of size, a direct role in gathering information about military forces and activities of concern to them."

Baker's description of the treaty's aims echoes Eisenhower's emphasis on the importance of transparency but also points to the treaty's utility for confidence building, as well as its importance for countries that may not have equivalent surveillance capabilities. This latter point was particularly salient because, by this time, both the United States and Russia had the ability to collect much of the same imagery that would eventually be collected under Open Skies provisions with satellites. A major implication of Open Skies was to be that countries without immensely expensive spy satellites would have the means to collect this same type of imagery, thus creating a more equal playing field in terms of information.

Between the simultaneous goals of treaty verification and confidence building, greater importance was initially given to the former due to the failure to include an aerial inspection component in the The Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty which was signed in November 1990. Directly prior to the CFE Treaty's signature, the Soviet Union had either physically moved or reassigned an enormous amount of personnel and armaments in order to place them outside the treaty's inspection authorities. Such actions underscored the desirability of a generalized regime for treaty verification.

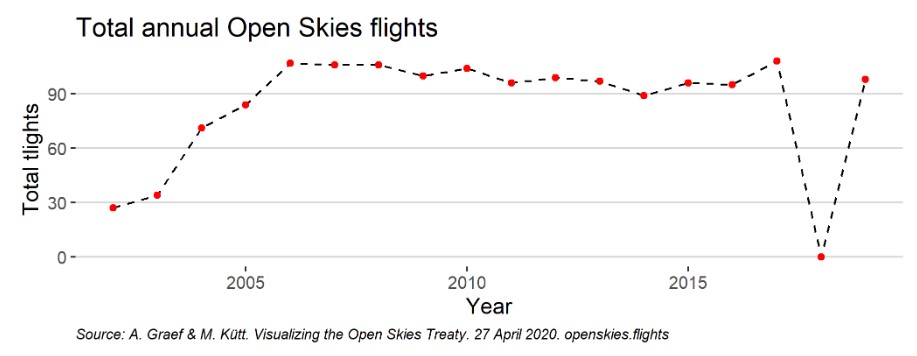

Though the CFE Treaty has essentially been defunct since 2007, there were 1,194 Open Skies flights between 2007 and 2019, demonstrating continued interest in the treaty and its utility for participants. Moreover, the provisions of the treaty have shown utility during international crises. For instance, in the 17 months after the Russia-Ukraine conflict over Crimea and Donbass over a dozen Open Skies flights took place over Ukraine and Russia, including "extraordinary" flights which are flights either requested by international organizations such as the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) or agreed to on a bilateral basis between countries that do not count against normal quotas. For their part, Russian officials pointed to these flights as evidence of their own transparency, even presenting imagery from one flight in order to underscore their position. While the events of this time remain disputed, the treaty allowed States Parties to have access to imagery that supported diplomatic engagement. Furthermore, Russia did not choose to leave the treaty, an indication that it continues to value the mechanism.

As stated earlier, military personnel from the host country may accompany the crew conducting an Open Skies flight. Those arguing in favor of Open Skies have pointed to these military-to-military contacts as crucial opportunities for the building of trust and relationships between often adversarial militaries. Such relationships can ideally facilitate the exchange of information regarding capabilities and intentions, thus avoiding states of uncertainty in which miscalculations and misinterpretations can be made.

Reasons for US Withdrawal

The stated reasons for US withdrawal from Open Skies center on a single actor: Russia. US officials have alleged repeated Russian non-compliance with the treaty's provisions, arguing that Russia has perverted the general spirit of the treaty and placed all of this behavior in a broader context of Russian aggression and violation of other arms control treaties.

Regarding non-compliance issues, Russia has been accused of blocking or limiting flights in a variety of instances. The blocking of flights over Kaliningrad and Georgia have been particularly contentious. In the case of Kaliningrad, where Russia has cleared land for military shelters and refurbished missile bases, Russian officials have limited the maximum distance of proposed flights to 500 kilometers since 2014 which, in practice, prevents any single flight from observing the entire territory. Russia has justified this by claiming previous flights that made use of the original maximum distance have zig-zagged over the territory in such a way that limits the region's limited civil aviation.

Meanwhile, Russia has prevented Open Skies flights from getting within ten kilometers of Russia's border with the Georgian regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, arguing that because Russia recognizes them as independent territories they are obligated under the treaty's provisions to prohibit such flights. These restrictions have been in place since 2010.

The US has responded to these alleged violations with restrictions of its own. For instance, in 2017 the US imposed limitations on flight distances over Hawaii to 900 kilometers while also blocking Russian access to air bases in Georgia and South Dakota that have been used to refuel Open Skies flights.

Beyond these alleged violations, US officials have argued that data collected by Russia Open Skies flight's are being used, as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated, "in support of an aggressive new Russian doctrine of targeting critical infrastructure in the United States and Europe with precision-guided conventional munitions." The act of using Open Skies flights to observe critical infrastructure does not itself violate the treaty. US officials have acknowledged this while they have also declined to provide examples of Russia engaging in such activities. However, Pompeo and other officials have claimed this use of treaty provisions for aggressive ends perverts the treaty's intended purpose of confidence and trust building.

Other criticisms emerged in 2014 after Russia began upgrading their imagery equipment for their Open Skies aircraft. As Russia was in the process of upgrading to digital imagery equipment from wet film, critics of the treaty alleged this improved capability would allow the Russians to collect information that would jeopardize US national security.

However, as noted earlier there are standardized limits on imagery resolution regardless of the device used to capture the image. Under Open Skies, both film and digital images would have the same maximum imagery resolution, while the US would have to certify the introduction of this new imagery device at the Open Skies Consultative Council and would have the opportunity to inspect it before any flight. Despite this, the issue came to a head in 2018 when the US refused to certify the new sensor, though the US eventually reversed course. Notably, this was part of a series of disputes that resulted in the suspension of all Open Skies flights in 2018.

US officials have also cited Russia's violation of the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty and Russia’s invasions of Ukraine and Georgia, among other transgressions, as evidence that the country is "no longer committed to cooperative security." This argument is notable for its breadth and would seem to imply a Trump Administration view that negotiated resolution of treaty disputes is simply not something Russian officials are interested in. As such, further efforts to bring Russia back into compliance with the treaty are futile, leaving only the option of American withdrawal.

Russia has responded to such accusations by pointing to a variety of alleged US violations of the treaty's provisions, including the aforementioned flight restrictions over Hawaii. They have also argued that a general animosity towards arms control agreements is behind the US decision to withdraw from Open Skies, comparing American attitudes towards arms control to those of the Soviet Union during the 1960's and 1980's. Under this view, it would seem the US decided to leave Open Skies and only then used allegations of Russian violations as retroactive justification.

The Future of Open Skies

Following the US' announcement of withdrawal from Open Skies, a dozen European countries released a joint statement explaining "We will continue to implement the Open Skies Treaty, which has a clear added value for our conventional arms control architecture and cooperative security. We reaffirm that this treaty remains functioning and useful." As such, it appears there is a continued commitment to the treaty on the part of Europeans.

This is an encouraging sign for the future of the treaty as Russia and Belarus (which constitute a single participant under the treaty) conduct more than 87% of their flights over Europe and Canada. Given that European countries also obviously conduct the vast majority of their flights over Russia/Belarus, continued participation in the treaty appears to be mutually beneficial for the remaining parties even without US participation.

However, US withdrawal was heavily criticized by Russia while it also created some new anxieties as well. Beyond stating that the US decision to withdraw was a "deplorable development for European security," Russia also argued that the decision "calls into question Washington's negotiability and consistency." This latter statement mirrors language from US statements mentioned above which seemed to question the utility of negotiations as a general matter.

Moreover, at this past month's meeting of the OSCC Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov expressed concern that the US would continue to receive imagery collected under the treaty's provisions even after leaving the agreement. While this represents one potential point of contention between Russia and the remaining treaty participants, the annual process for allocating active flight quotas was successful this year.

Though Open Skies appears more or less stable for now, this leaves the question of whether the US would be able to reenter the treaty in the future after President-elect Joseph Biden takes office in January 2021. Under Article X of the treaty it would appear that the US technically could reenter the treaty as this section states the OSCC will "consider and take decisions on applications for accession to this Treaty."

However, it is worth remembering that such a decision would requires the unanimous approval of the OSCC and given the lack of goodwill between the US and Russia related to the treaty this may prove difficult. Indeed, the head of the Russian Foreign Ministry's Conventional Arms Control Division stated this past July that "it will not be easy" for the US to rejoin the agreement.

Moreover, there would be considerable political challenges to rejoining the treaty within the US. The initial US accession to the treaty required ratification by the US Senate, meaning two-thirds of the legislative body had to consent to the treaty's provisions. Should the Biden administration seek to rejoin Open Skies by again seeking the advice and consent of the Senate, they would likely encounter significant opposition from Republican Senators.

Democrats will, at best, have 50 of 100 seats in the Senate after runoff elections in Georgia are concluded in early January 2021 while historic opposition to the treaty on the part of Senate Republicans makes it all but impossible that Democrats would be able to muster enough votes on the issue. Indeed, Senator Jim Inhofe, Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, and Senator Jim Risch, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, have both expressed support for President Donald Trump's decision to withdraw from the treaty.

Alternatively, there do exist legal arguments that the original consent of the Senate does not terminate with withdrawal from the treaty when withdrawal was initiated by the executive and the treaty itself still exists. Following this argument, the Biden administration could attempt to argue the 1993 Senate approval of Open Skies is still valid and he need only work through the OSCC to rejoin. The legality of this approach could still be attacked by domestic opponents of participation within the US. For instance, Senate Republicans could claim that rejoining in such a manner subverts the Constitution's Article II requirements and thereafter seek to block funding for Open Skies activities.

As of now, it remains unclear where, or even if, rejoining Open Skies would be on a Biden administration's list of priorities. Doing so would certainly square with Democrats' criticism of the Trump administration's "ill-considered withdrawals from critical arms control treaties and nuclear agreements," as well as a desire to improve relations with European allies. That being said, the Biden administration may prioritize other arms control issues, such as renewing New START, over Open Skies while they may also seek ways of improving relations with Europe that have fewer domestic political costs.